1965: (I can't get no) Satisfaction

1965: (I can't get no) Satisfaction

Unfortunately, 1965 started inauspiciously when wine's greatest living ambassador died at the age of ninety - Winston Churchill. His capacity for drinking was reknown as were his related quotations: 'remember it is not just France we are saving but also Champagne' and 'I must point out that my rule of life prescribed as an absolutely sacred rite smoking cigars and also the drinking of alcohol before, after, and if need be during all meals and in the intervals between them' which he reputedly announced during a lunch with the Arab leader Ibn Saud, on being told that the King's religion forbade smoking and alcohol. Harry Hopkins’s (one of Franklin Delano Roosevelt's closest advisers) papers contain many references to Churchill and his enjoyment of wine and its fortified varieties. In a memo from Churchill to Hopkins dated 21 January 1943 : 'Dinner. ... (Dry, alas!); with the Sultan. After dinner, recovery from the effects of the above.' The next day Hopkins arrived early at Churchill's residence to discover him 'in bed in his customary pink robe, and having, of all things, a bottle of wine for breakfast.' As if in revenge for the loss of such a great wine lover most of western Europe sustained one of the worst vintages ever. In Champagne the summer passed with severe storms, cold and hail. In Bordeaux it was catastrophically damp and cool, and Burgundy had one of the worst vintages on record. One would have to look to the west coast of the United States for something better.

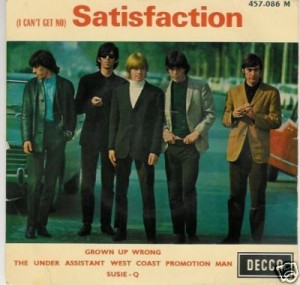

1965 was the year that Mick Jagger and Keith Richards wrote the hugely popular '(I can't get no) Satisfaction' which regularly features in the Top 100 most popular or seminal songs of the 20th century. It was the first hit song in the USA for the Rolling Stones. The title and content of the song is often erroneously construed as having strong sensual connotations whereas it was really a statement against the unchecked commercialism that Jagger witnessed in the United States during their tour there and when this song was written. It tries to illustrate just how luckless and alienated one can become if one doesn't conform to these consumer aspirations - Jagger's alienation complete with his line: 'When I'm drivin' in my car, and the man come on the radio, He's tellin' me more and more about some useless information. Supposed to fire my imagination'. Perhaps the 60s more than any other marked the start of 'commodification', a theme of this song, as social values are replaced by ones determined by their market value, but a word which only made it into the Oxford English dictionary a decade later even if its roots are founded in the philosophies of Karl Marx over a hundred years previously. As an antidote to the musical irreverence of the youth of their day, the rest of the world continued to live a normal life by making The Sound of Music, starring Julie Andrews, the biggest grossing film of the year.

The revolution played itself out in the decades that followed as Hell's Angels, drug-takers, revolutionaries and the scene setters of the 60s fermented into a maturing middle class, themselves turning the capitalist wheel complete with honours, knighthoods, gala evenings, royal patronage and the sartorial accoutrements of Range Rovers, Barbour jackets and green wellies. The predictions of sociologists and philosophers of the time conveniently forgotten as the icons of the era faded into a diaspora of contented bourgeoisie. So much for the counter-culture.

The Rolling Stones' arch rivals, The Beatles, continued to progress with their new album Rubber Soul, a title which was credited to Paul McCartney who had overheard another musician referring to the voice of Mick Jagger as 'plastic soul'. It was also the year the Beatles met with Elvis Presley for the first and last time. In the UK, apart from these two groups, the best selling artists that year included Elvis Presley, the Shadows, Bob Dylan, The Byrds, The Kinks, The Hollies, The Animals, Sonny and Cher, The Yardbirds, Marianne Faithfull, and Tom Jones. All these would continue to dominate the music scene for decades something which no popular music pundit might have predicted back then.

But it's hard to imagine the swinging 60s if you weren't actually part of it - 'Swinging' because just about anything went and as Jefferson Airplane's Paul Kantner commented: 'If you can remember anything about the sixties, you weren't really there.' This image sustained by the largely misunderstood slogan of Timothy Leary 'turn on, tune in, drop out' something he helpfully clarified in his 1983 autobiography Flashbacks: 'Turn on' meant go within to activate your neural and genetic equipment. Become sensitive to the many and various levels of consciousness and the specific triggers that engage them. Drugs were one way to accomplish this end. 'Tune in' meant interact harmoniously with the world around you - externalize, materialize, express your new internal perspectives. Drop out suggested an elective, selective, graceful process of detachment from involuntary or unconscious commitments. 'Drop Out' meant self-reliance, a discovery of one's singularity, a commitment to mobility, choice, and change. Unhappily my explanations of this sequence of personal development were often misinterpreted to mean 'Get stoned and abandon all constructive activity'. It's not hard to understand why no one grasped the true meaning at the time.

The price of wines in the 1960s had not yet put them in the status of asset-class. Berry Bros & Rudd, one of the UK's oldest wine merchants revealed that in 1965 they sold the following bottles: 1960 Chateau Latour or 1960 Chateau Mouton Rothschild for 42/6 (forty-two and six if you can't remember that far back or £2 2s 6d: £2.125 expressed as a decimal) , 1961 Ch. Cheval Blanc: 48/- (forty-eight bob; £2.4) 1961 Ch. Lynch Bages: 29/- (£1.45) per bottle 1961 Ch. Palmer: 30/- (£1.5) per bottle and 1961 Ch. Léoville Barton: 29/6 (£1.475) per bottle. Apparently quite cheap. However, if we convert these into today's money they look like this: 1960 Chateau Latour or 1960 Chateau Mouton Rothschild £28 at today's prices; 1961 Ch. Cheval Blanc: £32, 1961 Ch. Lynch Bages: £19, 1961 Ch. Palmer £20 and 1961 Ch. Léoville Barton £20. So, something has changed given that a bottle of the 2007 vintage of Chateau Latour would set you back just over two hundred pounds in today's money. That's almost ten times more than might be accounted for by inflation alone. In 1965 you could buy an E type jaguar for approximately £1850. In today's money that is £25,000. A gallon of petrol cost which cost around £0.24 then would cost £3.50 today if adjusted for inflation alone whereas in fact it costs just £5 (sic).

You can find wines from the 1965 vintage today, at generally inflated prices, perhaps sold for the purpose of celebrating some anniversary or other, like newspapers. One hopes they give some pleasure.