In a world increasingly dominated by globalisation and industrialisation it can be heartening to find participants in an industry which remains so much a family concern, managed by the descendants of those who established the reputations and traditions for excellence. A cursory glance at the labels of Champagne bottles in your local wine seller is a portrait gallery from the Champagne region and their ‘Maisons’ -- Bollinger, Taittinger, Billecart-Salmon, Duval-Leroy, Roederer, Paillard, Deutz and Henriot to name but a few. But not all the names continue to own or even work in the company which may bear their name.

Statistics speak for themselves. 90% of the Champagne region is owned by the ‘growers’ of grapes which may be used in Champagne and who may make Champagne too. There are 15,000 of these ‘growers’ of whom only 5,000 actually produce Champagne under their own name. The rest just sell the raw material. Of these 55% own less than one hectare. However, it is the ‘negoçiant manipulant’ of whom there are only 290 who account for two--thirds of all sales and 90% of exports.

Pierre--Emmanuel Taittinger is head of the eponymous firm Taittinger which is one of the best known in the region. They are also one of the largest, producing approximately five million bottles each year. Defying the trend of large corporations who have come in and bought so many of the large brands in Champagne he managed to persuade the Crédit Agricole to help him buy back his Champagne business in 2006. He thinks that his 31 years of experience counted strongly with his backers but so did his name and the fact he has children to whom the business will pass in the future. ‘The bankers knew that Taittinger without a family and spirit at its head would be different — not necessarily worse, just different.’ Taittinger believes that Champagne is also about ‘continuity and consistency. Being a family firm is a great guarantee of quality.’ The name of Taittinger is also a name associated with the social and political destiny of the region and is thus ‘part of the patrimony of the region. Essential,’ he argues, ‘that it should be restored to the family for its safekeeping.’ Clearly his bankers agreed.

Pierre--Emmanuel Taittinger is head of the eponymous firm Taittinger which is one of the best known in the region. They are also one of the largest, producing approximately five million bottles each year. Defying the trend of large corporations who have come in and bought so many of the large brands in Champagne he managed to persuade the Crédit Agricole to help him buy back his Champagne business in 2006. He thinks that his 31 years of experience counted strongly with his backers but so did his name and the fact he has children to whom the business will pass in the future. ‘The bankers knew that Taittinger without a family and spirit at its head would be different — not necessarily worse, just different.’ Taittinger believes that Champagne is also about ‘continuity and consistency. Being a family firm is a great guarantee of quality.’ The name of Taittinger is also a name associated with the social and political destiny of the region and is thus ‘part of the patrimony of the region. Essential,’ he argues, ‘that it should be restored to the family for its safekeeping.’ Clearly his bankers agreed.

Charles Philipponnat works for Champagne Philipponnat. His family have been making wine in the region since the beginning of the sixteenth century making a celebrated red wine in Aÿ which was even exported to England. When sparkling wine became popular in the second half of the nineteenth century his family started producing their own brand. Despite the problems which beset the region during the period from the late nineteenth century — Phylloxera, Word War I and the Wall Street Crash of 1929 —- Philipponnat managed to prosper buying several vineyards of which their ‘Clos des Goisses’ is the most famous. But the family was forced to sell up in the late seventies, the marque eventually passing to the Boizel Chanoine Champagne group. So, although it is no longer a family company, it is still headed by a member of the family which bears the same name as the Champagne brand and the group of which it is part, is owned by a Champagne family. Was this just coincidence? Philipponnat thought that there were still advantages to having the firm run by someone who is so closely identified with the brand. He felt this was as an important a reason as his fifteen years’ experience of negotiating grape contracts. Charles Philipponnat feels that when one is a member of the family one is even more motivated to make it work and there is no hiding from the responsibilities. For him, it is not just his life but the work of several generations he is now responsible for whilst continuing the family tradition. He feels the advantage is obvious. ‘The greatest advantage to a family run business unless one is mired in family quarrels, is that if the business is well--managed, then decisions can be taken very fast because day--to--day responsibilities lie in the hands of the shareholders themselves.’

Charles Philipponnat works for Champagne Philipponnat. His family have been making wine in the region since the beginning of the sixteenth century making a celebrated red wine in Aÿ which was even exported to England. When sparkling wine became popular in the second half of the nineteenth century his family started producing their own brand. Despite the problems which beset the region during the period from the late nineteenth century — Phylloxera, Word War I and the Wall Street Crash of 1929 —- Philipponnat managed to prosper buying several vineyards of which their ‘Clos des Goisses’ is the most famous. But the family was forced to sell up in the late seventies, the marque eventually passing to the Boizel Chanoine Champagne group. So, although it is no longer a family company, it is still headed by a member of the family which bears the same name as the Champagne brand and the group of which it is part, is owned by a Champagne family. Was this just coincidence? Philipponnat thought that there were still advantages to having the firm run by someone who is so closely identified with the brand. He felt this was as an important a reason as his fifteen years’ experience of negotiating grape contracts. Charles Philipponnat feels that when one is a member of the family one is even more motivated to make it work and there is no hiding from the responsibilities. For him, it is not just his life but the work of several generations he is now responsible for whilst continuing the family tradition. He feels the advantage is obvious. ‘The greatest advantage to a family run business unless one is mired in family quarrels, is that if the business is well--managed, then decisions can be taken very fast because day--to--day responsibilities lie in the hands of the shareholders themselves.’

Champagne production requires significant capital and this has been one of the difficulties for many families who have failed to organise their money in good time. For every 1.5kg of grapes already in the cellar one has to hold a further 3 kilogrammes (the approximate weight required to produce one bottle of Champagne is 1.5kg) where one might sell 1 of these in every 3 years. So the bankers have to be patient but the high cost of entry means the industry is also very stable. Right now there are still quite a few family owned businesses but one might ask what might happen in the future when the current generation moves on?

To be a woman in what most see as a man’s world has its special difficulties. Delphine Cazals is based in Mesnil, famous for its Chardonnay grapes where she is a grower and producer -- a ‘recoltant cooperative’. Delphine Cazals is not only the owner and CEO of her own business but is also married to a Champagne producer. A healthy rivalry exists between them and at the time she married most assumed that her business would be subsumed into her husband’s. What’s in a name for her?

To be a woman in what most see as a man’s world has its special difficulties. Delphine Cazals is based in Mesnil, famous for its Chardonnay grapes where she is a grower and producer -- a ‘recoltant cooperative’. Delphine Cazals is not only the owner and CEO of her own business but is also married to a Champagne producer. A healthy rivalry exists between them and at the time she married most assumed that her business would be subsumed into her husband’s. What’s in a name for her?

Cazals’ situation is a little complicated. Her marque is Cazals, the name of her forbears. Her married name is Bonneville. But her clients know her as Cazals which accords more with the modern fashion where women maintain their maiden name. But it still causes confusion. She has managed; although her husband bristles when people refer to him as ‘monsieur Cazals’. Her daughter, who might go into the business, is called Bonneville, the family name. But Cazals believes that the name she carries is important all the same because when someone meets here they say ---- ‘oh yes, it’s you’. Bonneville--Cazals is a little long. Each label carries her name as the winemaker too ---- ‘elaboré par Delphine Cazals’.

Benoit Tarlant feels that a family business is defined through the communication across the generations: in his case his father, grandfather and great grandfather. So for the Tarlants it’s not about discussing things outside the family with external advisors notwithstanding the so--called ‘generation gap’ and its attendant problems. He illustrates this by reference to their terrain. Some of his vines were planted in 1946 and so he knows little of their lives and it is something in which the older generation can help him to assess their potential. But even if there is this tradition in this respect the older generation of the Tarlant family stand back in allowing Benoit to find full expression in the wines he makes.

Benoit Tarlant feels that a family business is defined through the communication across the generations: in his case his father, grandfather and great grandfather. So for the Tarlants it’s not about discussing things outside the family with external advisors notwithstanding the so--called ‘generation gap’ and its attendant problems. He illustrates this by reference to their terrain. Some of his vines were planted in 1946 and so he knows little of their lives and it is something in which the older generation can help him to assess their potential. But even if there is this tradition in this respect the older generation of the Tarlant family stand back in allowing Benoit to find full expression in the wines he makes.

Roederer is one of the oldest Champagne houses having started in 1776 and produces the legendary Champagne Cristal. Frédéric Rouzaud, his family name does not appear on the bottle, is a direct descendant of one of the original family members. The business is family owned and run.

He didn’t seem to mind that he was not called Roederer or that the business suffered too much as a result. ‘Maybe its easier to have one’s name on the bottle because one doesn’t have to say it is a family affair all the time’. But they are discreet people too and almost prefer the consumer ignorance in this respect even if most people working in the Champagne trade would know he is the owner. He maintains that his sense of responsibility is the same and few could doubt him or argue with the company’s success. Roederer now own vineyards around the world and only recently purchased the celebrated Bordeaux château, Château Pichon Longueville Comtesse de Lalande. He didn’t feel the urge to attach his name in a demonstrative way to that wine either.

He didn’t seem to mind that he was not called Roederer or that the business suffered too much as a result. ‘Maybe its easier to have one’s name on the bottle because one doesn’t have to say it is a family affair all the time’. But they are discreet people too and almost prefer the consumer ignorance in this respect even if most people working in the Champagne trade would know he is the owner. He maintains that his sense of responsibility is the same and few could doubt him or argue with the company’s success. Roederer now own vineyards around the world and only recently purchased the celebrated Bordeaux château, Château Pichon Longueville Comtesse de Lalande. He didn’t feel the urge to attach his name in a demonstrative way to that wine either.

But, he felt very strongly that a family concern had different objectives. Ones which enabled them to engage in profitable and worthwhile long term projects which a non--family owned company would scarcely be able to contemplate. He cited the establishment of their sparkling wine brand in California which took 12 years to fulfil. He also cited a ‘kind of liberty with people sharing the same values, and the same passion.’ They are all part of a special ‘family culture of wine’.

Jean--Marc Lallier doesn’t feel too sad about lacking proprietorship of the Deutz brand but then he doesn’t carry the actual name even if he is a direct descendant of the founder. However, as part of the Roederer group, it is effectively a family company run and operated from within the region. Lallier also makes it clear that they are an autonomous unit. Their future secured they can focus on the quality rather than the return. Whilst he doesn’t lament the eponymous contact through direct identification with the name of Deutz he is very attached to the past and the development of the philosophy that they have always had and tries to perpetuate his ancestors objectives.

So what does he contribute to the firm and why have a family member on the Board of Directors? Lallier knows the European market well and the new owners at the time told him ‘we need you to stay and keep the style of Deutz’. He is, of course, the embodiment of that Deutz style down to his atavistic characteristics but much to his wife’s relief without the big long beard of his ancestor. Within a family business one ‘needs to have people around who understand where you want to go when it’s a question of continuity. Also, in a large company one is lost in a hierarchy which is not the case here.’

Jean Hervet Chiquet (Champagne Jacquesson) and his brother own 51% of their Champagne house. A business they inherited from their father who was a grower but had no involvement in the early founding of the brand. The Chiquets have ‘grower mentality’ which helps them buy in their grapes and in their relationships with the growers who supply them. Running the business is easy. ‘If I want to do something I just ask my brother and vice versa’. He doesn’t see the relationship between his name and that of the name on the bottle ---- the ‘commitment is the same’. Their personal philosophy about the style of the Champagne they make is distinctive from what a normal company structure would require. They make the wine they want and try and persuade the customer that this is the best wine for them. A company would almost certainly choose to make a wine that required no such explanation.

Jean Hervet Chiquet (Champagne Jacquesson) and his brother own 51% of their Champagne house. A business they inherited from their father who was a grower but had no involvement in the early founding of the brand. The Chiquets have ‘grower mentality’ which helps them buy in their grapes and in their relationships with the growers who supply them. Running the business is easy. ‘If I want to do something I just ask my brother and vice versa’. He doesn’t see the relationship between his name and that of the name on the bottle ---- the ‘commitment is the same’. Their personal philosophy about the style of the Champagne they make is distinctive from what a normal company structure would require. They make the wine they want and try and persuade the customer that this is the best wine for them. A company would almost certainly choose to make a wine that required no such explanation.

However, the association with a family name is significant for François Billecart--Salmon (Champagne Billecart--Salmon). ‘It is very important for me. It helps one to try and make the best product you can because you know one day you will be in front of your consumers with your name on the label.’ Of course, running a family firm can mean relations think it is a meal ticket.’ Not so at Billecart--Salmon. They don’t practise nepotism. But human problems are easily dealt with. As a family firm they can determine the kind of dividends they need to distribute. More problematic can be finding sources of finance. ‘It is limiting to only be able to call on the bank for money’. François Billecart-Salmon identifies five key areas where a family firm works best: ‘1. As it is not a big company they are of a size where they can keep things under control. 2. The family is in for the long haul. An investor when he comes in looks at the exit, as a result they can invest and work for the very long term. This helps for storing stock and when deciding to release a vintage — even after 10 years. 3. As a native of Champagne they have a lot of contacts with growers and this is important for a Champagne house. 4. The workload can be spread amongst the family 5. They share the same priorities.’

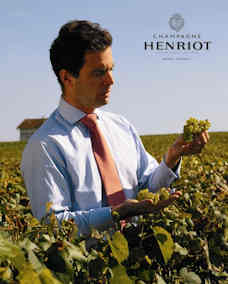

Stanislav Henriot’s family have been active in the region of Champagne for 300 years but it was only in 1908 that the Champagne house was formed. For him, there is no question of bringing anyone from outside the company to run it. But, the Henriots are a fecund family and this can cause problems of succession and division. Stanislav’s father’s sisters had 21 children between them. However, when the group was rebuilt, they established a structure to avoid problems associated with withdrawal of shareholders funds and a partition to protect the management of the company from shareholder action. Henriot thought that having a family member so obviously associated with the company was more important than ever. A genuine product is more than just a story that the brand can tell you. A person that can risk his name and he has a very strong link with their clients. His signature is on each bottle that he sends to the market.

Stanislav Henriot’s family have been active in the region of Champagne for 300 years but it was only in 1908 that the Champagne house was formed. For him, there is no question of bringing anyone from outside the company to run it. But, the Henriots are a fecund family and this can cause problems of succession and division. Stanislav’s father’s sisters had 21 children between them. However, when the group was rebuilt, they established a structure to avoid problems associated with withdrawal of shareholders funds and a partition to protect the management of the company from shareholder action. Henriot thought that having a family member so obviously associated with the company was more important than ever. A genuine product is more than just a story that the brand can tell you. A person that can risk his name and he has a very strong link with their clients. His signature is on each bottle that he sends to the market.

Bruno Paillard is unique in Champagne ---- as the name of the brand is also the name of the founder, the owner, and the winemaker. He comes from a long line of Champagne producers and has built up his company from scratch since it was founded in the 1980s. Today, they own 25 hectares of which 12 are grands crus.  He produces half a million bottles a year and exports 75% to more than 30 countries. Separate from growers’ champagne he stresses the importance of being a negoçiant because this is where the artistic creation comes into play, creating the blend. A negoçiant can buy grapes. As good as his own vineyards are he is happy to have access to other vineyards in order to create the aromas and taste which an ‘assemblage’ will give him. If he owned 75 hectares he would be happy too. His balance sheet would be more ‘beautiful’ but they would also have to be located in the most ideal locations. He would be self-sufficient but it might be more difficult to achieve the level and quality that his wine achieves now — an odd paradox.

He produces half a million bottles a year and exports 75% to more than 30 countries. Separate from growers’ champagne he stresses the importance of being a negoçiant because this is where the artistic creation comes into play, creating the blend. A negoçiant can buy grapes. As good as his own vineyards are he is happy to have access to other vineyards in order to create the aromas and taste which an ‘assemblage’ will give him. If he owned 75 hectares he would be happy too. His balance sheet would be more ‘beautiful’ but they would also have to be located in the most ideal locations. He would be self-sufficient but it might be more difficult to achieve the level and quality that his wine achieves now — an odd paradox.

When Paillard started his business the important thing was to gain access to quality grapes and this was not a matter of money. It’s a question of being accepted by the growers when they have everyone queuing at their door and ultimately growers are very loyal to their customer base — 90% of contracts are renewed with the same buyer. Back in 1980s it was comparatively easy to develop these relationships but today it is a different situation because Champagne has become so successful and it will be a long time before more grapes may become available. Money would not help. Being part of the wider Champagne family does.

Not everything is plain sailing in a Champagne family. Investment can be hard in a business where some years the quality may be better than others. This is more marked for a grower than a negoçiant who through the use of the assemblage can disguise some of the year’s poorer qualities. What’s worse is that family inheritances can cause problems. But Champagne is still largely a family affair and likely to remain so for the future.

We spoke to:

Pierre Emmanuel Taittinger — Champagne Taittinger

Charles Philipponnat — Champagne Philipponnat

Delphine Cazals — Champagne Cazals

Carole Duval--Leroy — Champagne Duval--Leroy

Benoit Tarlant — Champagne Tarlant

Frédéric Rouzaud — Champagne Roederer

Jean--Marc Lallier — Champagne Deutz

Jean--Hervet Chiquet — Champagne Jacquesson

Stanislas Henriot — Champagne Henriot

François Billecart--Salmon — Champagne Billecart-Salmon

Bruno Paillard -- Champagne Bruno Paillard

Fabian Cobb