Italy is a country of enormous diversity - geographic, cultural, linguistic, culinary and, of course, vinous. This applies to their sparkling wine production as much as their mountains, art, cities, dialects, salamis, cheeses and tranquil wines. In the current global economic crisis, Italian bubbly has shown strong export growth in in the first nine months of 2009 - up 14% in volume terms compared to 2008. This article looks at the background to the development of sparkling wines in Italy, the current state of the market and some of the reasons for its success.

Please see our reviews of some specific wines and producers which are listed FineWineMagazine.com.

Introduction

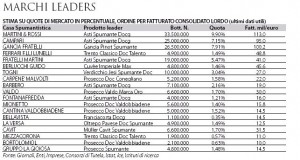

Wines made from the regions of Piemonte (Asti) and Veneto (Prosecco) are the market leaders (See table below)

Giampietro Comolli of the Forum Spumanti d'Italia is sure that the last 5 years have been fairly critical in the context of the 150 years since the first bottle was popped. During this time there has been a particular effort to align production to its geographical origin . So, whilst the bigger players - Martini & Rossi, Gruppo Campari, Gancia, F.lle Martini, to name just a few (see table of market leaders) established their brands in the 1980s using assemblage from different zones this has now changed into regional branding. But an Italy of mille commune as once declared Machiavelli, is an individualistic country. As if to demonstrate this there are some 278 DOC/DOCG zones which can produce at least one spumante, 20 regions produce spumante, 90 provinces are involved in making spumante and 500 commune produce grapes which end up in the various spumanti It's worth pointing out here that Comolli and many of his colleagues don't really like the term spumante – it's not even permitted in Franciacorta, and depending on the production method he prefers metodo classico - where the second fermentation is in the bottle - and metodo italiano (over Charmat, or even Martinotti) where the second fermentation is done in tank. Thus, one can find sparkling wines made from Ribolla Gialla in Friuli, or from Chardonnay grown at 800m above Palermo in Sicily; sparkling wines are made on the island of Ischia, in the Bay of Naples to the frontier valleys of Val d'Aosta. Just as wines are made lighter and fresher, a changing culture has accepted that sparkling wines of all types may be drunk pre/post-prandial and with foods of all description. Comolli believes that the future of sparkling wine from Italy rests upon three main thrusts: the implementation of procedures to continually improve quality; innovation and lastly, continued diversification.

Production and exports

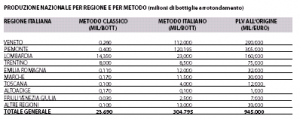

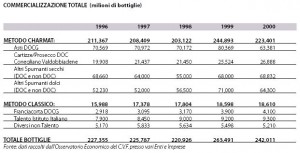

In pole position is sparkling Prosecco, whether DOC or not, with 160 million bottles (45% of total sparkling wine produced in Italu). Asti DOCG is top of its class with slightly under 76 million bottles produced, followed by Conegliano Valdobbiadene DOC Prosecco, with almost 50 million bottles. As to the metodo classico, leadership is shared by Franciacorta and Trento, with 9.7 and 8 million bottles, respectively. Veneto is the first Italian region in terms of production and consumption. Altogether in 2008 over 328,5 million bottles were produced (Italy being the 3rd lasrgest producer in the world), 304,8 millions of which pertain to the metodo italiano (or Charmat) method. Italy is also the 2nd largest exporter in the world. The European home market, with 27  countries, absorbs 70% of total exports.

countries, absorbs 70% of total exports.

The Big Brands

Mark Holdsworth, marketing manager at Bacardi-Martini is, of course, aware of the success of Italian bubbles. Their company has recently launched two new products into the UK market - a Prosecco DOCG and Rosé. He quoted the recent Multiple Grocers Data figures from Nielsen: Australian up 2.4% (by value), Spanish up 12.3% and Italian up 15.9% - “this is the success of Prosecco bringing up the category. Rosé too, in the broadest terms, has been in rude health”. In addition to the new launches Martini have completely repackaged the Martini Asti bottle (using foil and a higher quality bottle) and have distinguished the Martini brand on all of its labels. Holdsworth sees their branding as “an important element in a market which hitherto has not been a branded market.” As if to prove it, Martini have doubled their investment behind their brand.

Gancia

Carlo Gancia, the founder of the firm 150 years ago, learnt his winemaking in Reims, applying their techniques to the grape grown locally, moscato. Thus was born the first spumante italiano in 1865. In 2008 the company appointed two new directors whose task was to relaunch Gancia onto the world stage. In 2009 they have launched two new lines: the Cuvée Platinum (Asti DOCG Millesimato; Carlo Gancia Metodo Classico Brut and Prosecco di Valdobbiadene) and Spumanti Metodo Classico Alta Langa Gancia available in 5 versions. The strategy and production of Gancia would make an article on its own but needless to say their strategy fulfills the destiny of the new order in Italian sparkling wines.

Sgr Giancarlo Moretti Polegato presides over the family company of Villa Sandi. Based in Treviso they produce a number of DOC wines including Prosecco (DOCG) and the new Prosecco DOC (inter-regional wine from the Veneto and Friuli). “As far as Prosecco is concerned there has been a steady increase in sales over the last 5 years”. They also own La Gioiosa (producers of Prosecco but also still wines) which is now present in more than 60 countries worldwide. As further evidence of the state of this market they managed to increase their turnover by 12% in 2009 “primarily as a result of the strength of Prosecco. However, the popularity of Prosecco is not only because of its price, but because it's easy, young and women like it too.” He stresses the pride that has been brought to the Veneto region as a result of the affirmation of the geographical connection of 'Prosecco' – no longer just a grape variety (in fact the old name for the grape, glera, is now being used).

Metodo classico

By far the largest production method is metodo italiano (Charmat)– almost 9 bottles out of every 10 of sparkling wine are produced this way. However, spumante in Italy originated in the form of metodo classico.

The most famous regions for this style of sparkling wine now come from Lombardy (Franciacorta) and Trentino (Trento DOC). Maurizio Zanella (owner of Ca' del Bosco) and President of the Consorzio per la tutela del Franciacorta (with DOCG status) admits that in the UK Franciacorta is virtually unknown. Whilst in Italy Franciacorta on most good restaurant wine lists is de rigueur most British restaurants prefer to carry Prosecco. Even in 2009 Franciacorta held its own in a domestic market which has seen an overall decline of 20-25%. Zanella doesn't like comparisons with Champagne: “We're a different product. Different terroir and different production techniques with different yields and aging requirements. Champagne distribution is also significantly different.” Italy absorbs nearly all of their production, most are sold on-trade or in small markets, wine bars and shops.

Main varieties and regions

• Pinot Nero – Oltrepò Pavese (DOC and DOCG), Friuli

• Pinot bianco – Franciacorta (DOCG), Trentino (Trento DOC) and Alto Adige

• Chardonnay – Franciacorta (DOCG), Trentino (Trento DOC) and elsewhere

• Moscato – Asti (DOCG), Cuneo and Alessandria

• Glera (Prosecco) – Friuli and Veneto (DOC) and Conegliano-Valdobbiadne (DOCG)

Matteo Lunelli is the third generation in his family company, Ferrari, which was founded in 1902 by Giulio Ferrari who sold the business to Lunelli's grandfather in 1952. From the start Ferrari wanted to make wine using metodo classico and he was the first one to start this in Trentino. Ferrari was also the first to cultivate Chardonnay in Italy which he brought back from his visits to Champagne. He felt that the area of Trentino was unique in providing good growing conditions for two of the main Champagne varieties including Pinot Noir (known as pinot nero in Italy) - “the vineyards are in the hills which gives the different temperatures between day and night which help to develop acidity and aromatic maturation.” In 2007 Ferrari surpassed 5m bottles sold. “The British market is still very focussed on Champagne but we believe it is a good market in the future. We continue to innovate and launch new products. When someone asks me at Vinitaly what is new this year, I reply that we tried to make the wine as good as last year and the second thing is we tried to make it even better.”

Tasca d'Almerita, both the name of the family owners and the company, are an example of what might be done even in a region which is totally unknown for its production of sparkling wine – Sicily. Whilst their main wine, Regaleali is well established they now produce 40.000 bottles each year of a sparkling wine – Almerita brut - (out of a total of 2m+ bottles of their other wines) using the metodo classico and Chardonnay grapes. “We started the project with 5,000 bottles in 1989 , it was a game …unthinkable. Immediately all the sparkling wine world was really surprised by the style and the consistency of the Almerita and step by step it became very popular.”

The Italian way (a new approach)

Manlio Collavini presides over his family company which produce approximately 400k bottles of sparkling wines each year out of a total production of over 1m bottles of other wines. They started “to play” in the 1970s. For them the metodo classico was always something of a copy of Champagne. They now like to think of their wines as being made according to the “metodo Collavini” using in one case an autocthonous variety in Friuli – Ribolla Gialla. They now produce 70k bottles of this wine each year rising to 100k by 2013. Their production is based on the metodo italiano but it takes over 3 years to make a bottle. According to Collavini “if Dom Perignon had known of the autoclave (the pressurised enclosed tank at the heart of the metodo italiano) he would never have invented the methode Champenoise.” They have just started to produce a Prosecco.

Conclusion

Giampietro Comolli recently summed up his views on Italian spumante thus. “more than ever people are looking for sparkling wines which are higher in quality and better value – the price level is fundamental. Also, good distribution, clear labelling, and a range of wines which are more in keeping with international taste and world culinary developments.” This is undoubtedly the strategy behind all the companies we feature in this article. There exists an incredible diversity which can satisfy all the demands of an inquisitive public. The quality of the wines being made today under the rules of the various regions is very high – often exceptional. As W H Auden once said: “civilizations should be measured by the degree of diversity attained and the degree of unity retained.” On that basis, Italy is a truly outstanding example of a sparkling civilisation.

by Fabian Cobb (January, 2010)

This article was first published in The Drinks Business in March, 2010.

Pricing comparisons

A survey carried out in the City of London last August showed consumers possessed a good knowledge and attraction for Prosecco. Prices for Prosecco in some restaurants varied from £21 to £40. The UK was the 3rd importer for Italian sparkling wine in 2008, with 16m bottles, which has increased by a further 27% in the first 9 months of 2009 (the USA recorded a 40% increase in the first 9 months of 2009). Despite this, present in only certain supermarkets and restaurants, Italian sparkling wines are hardly widespread. Whereas some Italian sparkling wine price points in the multiples varied between £8.99 to £21.40 (for wines imported at £2.90 and £7.80 respectively), Champagnes (not reserve or vintage) were often listed in the same outlets for between £14.00 and £29.50. “Significantly”, a sparkling wine produced in Kent was selling for £18.99. One can’t expect much price evolution from Italian bollincine over the years as it is a product made on a grand scale (using industrial processes for the most part). Indeed, over a ten year period from 1995-2005 (during which the Lira also mutated into the Euro) the average price has increased by a modest 1-2%. Whereas in Champagne there has been a fairly constant increase of 5-6% per annum, almost a doubling of its price in the same period.